Indigenous Modernisms: Histories of the Contemporary brings together an international group of scholars, curators and artists to explore the relationship between histories of Indigenous modernisms and the artistic conditions of our own era. Why and in what ways did Indigenous artists in New Zealand, Australia, North America, Africa and the Pacific Islands embrace modernism or choose to modernise their own visual traditions, and what is their legacy for contemporary Indigenous artists today? How do these histories complicate and challenge our understanding of ‘the contemporary’? It is true that Indigenous modernisms deserve to be understood in their own contexts. But they increasingly matter to ours as we reexamine the question of indigeneity in a global art world.

The Indigenous Modernisms: Histories of the Contemporary symposium is a collaboration between the Art History Programme, Victoria University of Wellington, the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, and the ‘Multiple Modernisms: 20th Century Modernisms in Global Perspective’ research project. The symposium is convened by Peter Brunt and Megan Tamati-Quennell.

INDIGENOUS MODERNISMS: HISTORIES OF THE CONTEMPORARY

Soundings Theatre 11-12 December 2014

9.00am – 5.30pm

Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, Wellington

Thursday, 11 December 2014

8.30am. Registration, Soundings Theatre foyer, Level 2, Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

9.00am. Mihi whakatau/welcome from Ngāti Toa iwi kaumātuaTe Waari Carkeek and Rihia Kenny, with support from Dr Arapata Hakiwai, Kaihautū, Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, and Professor Piri Sciascia, Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Māori), Victoria University of Wellington

9.30am. Keynote 1: ‘Another Part of the Circle’: Positioning the Native Modern and the Contemporary Indigenous In and Out of (Art) History, Ruth Phillips, Carleton University

10.30am. Refreshments

11.00am. The End of Modernism: Western Desert Painting, Ian McLean, University of Wollongong

11.30am. Choice! Contemporary Māori Art and a Crisis of National Identity, Lara Strongman, Christchurch Art Gallery

12.00pm. Staring at Motorways: Urban Pacific Art – A Genealogy of Sorts, Nina Tonga, Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

12.30pm. Lunch (reconvene at 2.00pm)

2.00pm. In Conversation: Richard Bell, Josh Milani, and Ian McLean (moderator) on appropriation, modernism, and indigenous art in the contemporary field

This conversation is in honour of Gordon Bennett, 1955–2014

2.45pm. Retromodernism as Temporal Predicament, Elizabeth Harney, University of Toronto

3.15pm. After Modernism: El Anatsui’s Metal Sculptures and Sankofa Ideology, Chika Okeke-Agulu, Princeton University

3.45pm. Refreshments

4.15pm. Poles Apart: Realism and Figurative Abstraction as Modes of Modernity among Mid-20th-Century South African Artists, Anitra Nettleton, University of Witwatersrand

4.45pm. In Conversation: Katharina Greven, Chika Okeke-Agulu, and Nicholas Thomas (moderator) on the legacy of Georgina Beier and Ulli Beier in Nigeria and Papua New Guinea

5.30pm. Day 1 ends

Friday, 12 December 2014

8.30am. Registration, Soundings Theatre foyer, Level 2, Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

9.00am. Keynote 2: Dancing Around My Name: Indigeneity and Cosmopolitanism in the Life and Work of Aloi Pilioko, Peter Brunt, Victoria University of Wellington

10.00am. Reconfiguring the Art of ‘Zulu’ Carving: Assembled Headrests from the Msinga Region of Present-Day KwaZulu-Natal, Sandra Klopper, University of Cape Town

10.30am. Refreshments

11.00am. Back to the Future: Terry Ryan in Cape Dorset, Norman Vorano, Queens University

11.30am. ‘Genuine’ Inuit Artists: The Prevailing Discourse of Mid-Century Modernist Primitivism in the Arctic and the Curious Case of Contemporary Labrador Inuit Art, Heather Igloliorte (Inuit, Nunatsiavut Territory of Labrador), Concordia University

12.00pm. Māori Art: Infinite Creativity, Ngahiraka Mason, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tamaki

12.30pm. Lunch (reconvene at 2.00pm.)

2.00pm. Secrecy and Revelation: Joe Herrera’s Pueblo Modernism, W. Jackson Rushing III, University of Oklahoma

2.30pm. In Conversation: Paratene Matchitt, Shane Cotton, and Megan Tamati-Quennell (moderator) on the work of the late Ralph Hotere

3.15pm. Refreshments (15 minutes)

3.30pm. Resisting Modernisms: Strategies within Contemporary Māori Art, Anna-Marie White, The Suter Art Gallery

4.00pm. Ceremony as History in the Art of Edgar Heap of Birds, Bill Anthes, Pitzer College, Claremont University

4.30pm. In Conversation: Terry Smith, Ruth Phillips, Shane Cotton, Christina Barton, Chika Okeke-Agulu, Elizabeth Harney, and Geoffrey Batchen (moderator) on indigenous art and the contemporary art world

5.30pm. Symposium ends

Ceremony as History in the Art of Edgar Heap of Birds

Bill Anthes Professor of Art History, Pitzer College

A spate of recent historical projects – exemplifying what Hal Foster terms an ‘archival impulse’– in the work of Native North American contemporary artists such as Edgar Heap of Birds (Cheyenne-Arapaho, b. 1954) link to questions of time and temporality current in contemporary art practice broadly, as well as the historical periodisation of the contemporary as distinct from the modern. While recent critical writing on the contemporary has assumed that what Terry Smith describes as the ‘proliferation of asynchronous temporalities,’ is best understood through the discourses of political economy, communications and technology, and globalisation, indigenous contemporary artists offer an evocative counter-example. Seen in light of indigenous epistemologies, Native North American artists’ explorations and expressions of distinct ways of being-in-time expand the horizon of the contemporary, linking to often overlooked histories of indigenous modernisms and modernities. Moreover, in Heap of Birds’ work, the contemporary is seen as continuous with the deep past, as well as with a future understood as a cycle of return, as the work of history is linked to the practice of ceremony, and the human commitment to ensure renewal through mindful attention to the performance of ritual. This paper explores Heap of Bird’s engagements with history, and with notions of historicity and time as lived and imagined, and suggests that the question of the contemporary might be framed differently as indigenous modes of historical thinking are brought to bear.

Bill Anthes is Professor of Art History and a member of the Art Field Group at Pitzer College. He is author of Native Moderns: American Indian Painting, 1940-1960 (Duke University Press, 2006) and contributing author to Reframing Photography: Theory and Practice, by Rebekah Modrak (Routledge, 2011). His essays and reviews have been published in American Indian Quarterly, Art Papers, Art Journal, Exposure, Journal of the West, Number: An Independent Journal of the Arts, Visual Anthropology Review and other periodicals and exhibition catalogs. He has received fellowships and awards from the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum Research Center, the Center for the Arts in Society at Carnegie Mellon University, the Rockefeller Foundation/Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, and the Creative Capital/Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant Program. His book on the Cheyenne-Arapaho contemporary artist Edgar Heap of Birds will be published by Duke University Press in 2015. He lives in Los Angeles, California.

Dancing Around My Name: Indigeneity and Cosmopolitanism in the Life and Work of Aloi Pilioko

Peter Brunt, Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand

Aloï Pilioko (1935- ) is a groundbreaking indigenous modernist who forged a unique artistic practice in the early 1960s. From his village origins on the island of Wallis he ventured into the township capitals of the French Pacific – Port Vila, Noumea and Papeete – in the late 1950s and early sixties to discover a small but vibrant network of cosmopolitan modernists from a variety of mixed-up backgrounds. Entering this milieu, he went on to become one of its most famous and original exponents, assuming the identity of an almost classic modernist: a ‘man of the world’, a ‘painter of modern life’, a radical individualist, a global flâneur. Travel and cosmopolitanism are not usually associated with the concept of indigeneity, with its strong connotation of attachment to place; the ‘native’ stays put while the cosmopolitan travels the world. Pilioko turns that stereotype on its head. With his mentor and partner, French-Russian artist and collector, Nicolaï Michoutouchkine, he embarked on a four-decade career from the 1960s to the 1990s of continuous global travel and exhibition. Yet the concepts of home and indigeneity never stop being important to Pilioko; nor indeed to his more radically displaced travelling partner, Michoutouchkine. This paper explores the tensions between indigeneity and cosmopolitanism, ‘home’ and travel, here and elsewhere in their unusual project together.

Peter Brunt is Senior Lecturer in Art History at Victoria University of Wellington where he teaches and researches the visual arts of the Pacific, with an emphasis on the ‘post-colonial’ era. He received his PhD from Cornell University and is a 2014 Visiting Fellow of Clare Hall at the University of Cambridge. He is co-editor of Art in Oceania: A New History (2012), winner of the 2013 Art Book Prize in the UK, and Tatau: Photographs by Mark Adams: Samoan Tattoo, New Zealand Art, Global Culture (2010). He has published widely on the contemporary arts of the Pacific in journals, edited books and exhibition catalogues. He is also co-curating, with Nicholas Thomas and Adrian Locke, the exhibition Oceania at the Royal Academy of Arts, London, in 2018.

Retromodernism as Temporal Predicament

Elizabeth Harney, University of Toronto

Drawing on what Ali Mazrui has called ‘temporal homesickness,’ this paper addresses the ethos of retromodernism, a reflexive attitude evident within much African contemporary artistic practices and discourses. I argue that this phenomenon, premised on the perceived or real failures of the modernist project in Africa, is both a mechanism for articulating contemporary desires of return—a resumption of thwarted promises—and a means of sating the art world’s continuing appetite for revival, difference, and universality.

In the hands of critics, it retains the spectre of primitivism, making both a spectacle and a fetish of African modernity as an anachronism—a project cut unnaturally short by circumstance and painstakingly held apart from the tangible political and ethical effects of the loss of empire at mid-century. In the hands of artists, the playfulness and levity of the ‘retro’ belies the seriousness of its aim. Rather than simply a recap of postmodernist appropriation and pastiche, a trendy practice of archival mining, or an anti-imperialist nostalgia, retromodernism is a tool with which to make claims not just to modernity’s pasts (its ambitions, its certainties and fears, its genres) but also its futures (possibilities for regeneration, re-signification, and revolution). While some practices interrogate the materiality of colonial-modern archive, others engage the formal or conceptual legacies of modernism. Whether couched in the form of artists’ institutional ‘interventions’ or articulated in curatorial and scholarly agendas to demarcate a canon, critical journeys back in time now mark a measure of being ‘in time’ and ‘of the moment.’

Elizabeth Harney is an art historian and curator in the Department of Art, University of Toronto, teaching modern and contemporary African and diasporic arts. Harney is the author of In Senghor’s Shadow: Art, Politics, and the Avant-Garde in Senegal, 1960-1995 (Duke 2004) and Ethiopian Passages: Contemporary Art from the Diaspora (Philip Wilson/Smithsonian Institution: 2003) and co-editor of Inscribing Meaning: Writing and Graphic Systems in African Art (5 Continents Press, 2007). Harney has published in Art Journal, African Arts, NKA: Journal of Contemporary African Art, The Art Bulletin, Third Text, South Atlantic Quarterly and the Oxford Art Journal. She was the first curator of contemporary arts at the National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian (1999-2003). As a Commonwealth Scholar, Harney received her doctorate from the University of London. She has two books in progress, Retromodernism, Africa, and the Time of the Contemporary and Prismatic Scatterings: Global Modernists in post-war Europe.

‘Genuine’ Inuit Artists: The Prevailing Discourse of mid-Century Modernist Primtivism in the Artic and the Curious Case of Contemporary Labrador Inuit Art

Heather Igloliorte (Inuit, Nunatsiavut Territory of Labrador) Concordia University

Labrador Inuit art presents a remarkable instance in which we can examine the influence of mid-century modernism in the Canadian Arctic by comparing two neighbouring groups of Inuit: one which was heavily impacted by the influx of modernist mentors who moved into the Arctic in the 1950s and stayed to run studios and lead art co-operatives; another which was completely overlooked by the most influential art movement ever to impact Canada’s North. When ‘primitive’ arts entered into the discourse of modern art in the mid-twentieth century, Inuit stone sculpture (and later prints, and then drawings) in the North West Territories flourished under the tutelage, marketing, funding and tireless advocacy of Qallunaat (white) modernist instructors. Yet Labrador Inuit were wholly excluded from this development because at that time it was largely believed that there were no remaining ‘primitive’ Inuit, and consequently no ‘authentic’ Inuit art, in Labrador. It was only at the end of the twentieth century that Nunatsiavummiut (Labrador Inuit) began to gain recognition as ‘genuine’ Inuit artists, finally gaining the right to use the authenticating ‘igloo tag’ on their works and to otherwise market their work as ‘Inuit art.’ Consequently, Labrador Inuit artists have only just begun to enter into the discourse of contemporary Canadian Inuit art.

This paper traces the histories of modernism across two of the four Inuit territories to examine its impact in comparative analysis. How important was mid-century modernist primitivism to the development of contemporary Inuit art, and how different would Inuit art look today if not for the concerted influence of Qallunaat modernist mentors in the Arctic in the 1950s, 60s, and beyond? Does Nunatsiavummiut art provide a challenge to contemporary Inuit art, long defined by the tenets and impacts of modernism and primitivism in the Canadian Arctic?

Heather Igloliorte (Inuit, Nunatsiavut Territory of Labrador) is a Concordia University Research Chair in Indigenous Art History and Community Engagement in the Department of Art History at Concordia University in Montreal, Quebec. She completed her PhD in Cultural Mediations at Carleton University’s Institute for Comparative Studies in Literature, Art and Culture in 2013; her dissertation contributes the first art history of the Nunatsiavummiut, focusing on over 400 years of post-contact production, Nunatsiavummi Sananguagusigisimajangit/Nunatsiavut Art History: Continuity, Resilience, and Transformation in Inuit Art. Heather is also an active independent curator. Her recent projects include reinstalling the Brousseau Inuit Art Collection at the Musée National des Beaux-Arts du Québec (opening 2015), aboDIGITAL: The Art of Jordan Bennett (2012), and Decolonize Me (Ottawa Art Gallery, 2011 – 2015). Some of her recent publications include book chapters and catalogue essays in Negotiations in a Vacant Lot: Studying the Visual in Canada (2014); Manifestations: New Native Art Criticisms (2012); Changing Hands: Art Without Reservation 3 (2012); and Inuit Modern (2010).

Reconfiguring the art of ‘Zulu’ carving: Assembled headrests from the Msinga Region of present-day KwaZulu-Natal

Sandra Klopper, University of Cape Town

In the early 1970s, a migrant from the Msinga region of present-day KwaZulu-Natal began to assemble headrests from a variety of industrial off-cuts, selling them as wedding gifts to other Johannesburg-based migrants from the same rural district. Although remarkably similar in form to carved, monoxylic headrests from the same area, they are all highly inventive, introducing cultural and cross-cultural references in playful, but also richly suggestive ways. One example includes carefully selected newspaper cuttings mounted behind transparent sections of brightly coloured Perspex, among them scenes of coastal landscapes and urban entertainment, while another doubles up as a transistor radio. In this presentation I take a close look at several of these idiosyncratic headrests, exploring the significance they are likely to have had for their original patrons. But I also pose questions about their afterlife: assembled artefact entering a secondary market dedicated to the celebration of ‘authentic’ artworks. As I demonstrate, this market has responded in complex, but arguably predictable ways, to the creativity of rural migrants who produced works that are self-consciously modern.

Sandra Klopper specialises in African Art History. Her publications include books on South African art, such as Amandebele, The Bantwane – Africa’s Unknown People and African Renaissance, as well as numerous chapters in books and articles in accredited journals. She has been involved in various exhibitions and was a chief curator for the exhibition Democracy X: marking the present, representing the past (2004-05) – which was chosen by the Royal Academy in 2004 as one of the 15 must-see international exhibitions. Her research has been supported by awards and grants from the Human Sciences Research Council, the National Research Foundation, and the Technology and Human Resources for Industry Programme. Sandra received her PhD at the University of the Witwatersrand in 1992 and is currently Deputy Vice-Chancellor at the University of Cape Town.

Māori Art: Infinite Creativity

Ngahiraka Mason Indigenous Curator, Māori Art, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki

The 20th century period called Modernism has been productive for calibrating modern and contemporary Māori art to theoretical discourse in the academy and the art museum sector. Modern and contemporary Māori art have been abstracted, classified, interpreted, institutionalised and coveted by these sectors. Despite this, Māori art inhabits the outer edges of the canon of New Zealand art. Today, the building of institutional thinking is problematised by a cultural revitalisation of Māori art, culture and scholarship supported by the Treaty of Waitangi (New Zealand’s founding document) and a worldwide movement of indigenous rights including a reclaiming of indigenous knowledges by indigenous peoples. Guidelines for indigenous knowledge researchers are established (Smith), and Māori art scholarship (Mead) is also established and attended to in the academy.

This presentation addresses the importance of Māori scholarship for Māori people to whom Māori art belongs. Māori art is part of Māori culture which are the agreed upon practices of Māori people that have endured through time. Within this paradigm resides the infinite creativity of Māori people past, present and future – heritage, modern and contemporary.

Ngahiraka Mason is Indigenous Curator, Māori Art at Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki. Her first exhibition was Urewera Mural: Colin McCahon. Ngahiraka is a trustee on Te Māori Manaaki Taonga Trust. The Trust was established after the watershed exhibition Te Māori: Māori Art from New Zealand Collections (1984-87) to ‘encourage and provide for education and training of Māori in the skills required for the care and display of taonga Māori’. Her curatorial interests strongly relate to old knowledge and new understandings within indigenous sites of knowledge, to generate awareness of the value of culture.

The End of Modernism: Western Desert Painting

Ian McLean Senior Research Professor of Contemporary Art, University of Wollongong

In the 1980s the Western Desert painting movement that had begun at Papunya in 1971 was explained in terms of Western modernism. Critics compared it to everything from abstract expressionism to the conceptual art with which it was contemporary. There were good reasons for this. These large abstract acrylic paintings on canvas looked like late Western modernism and were a radical departure from traditional ceremonial art. Not only did other Western desert communities reject the art as too radical but also the art showed many signs of the pictorial experimentation associated with the modernist mindset. Further its artists, along with the new wave of contemporary Western artists, seemed to be engaging with each other in the transcultural fashion associated with the latest postcolonial theory.

In the 1990s, by which time other communities had begun to make acrylic paintings, the apparent modernism of the art was dismissed as a form of critical colonialism, and instead the art was interpreted in very traditional terms. If anything it was now seen as anti-modernist in the most conservative and reactionary sense of the term and transcultural engagements, even by urban indigenous artists, were discouraged. This remains the case. Desart, which is the Aboriginal-run body that overseas the now 40-odd desert art centres, proclaims on its website: ‘Aboriginal traditional law or culture is the foundation for all the art.’ In 2012 Nicolas Rothwell, reported Hector Burton and some other old men from Tjala Arts at Amata saying that the purpose of the art is ‘to defend their children and grandchildren from the dark temptations of modernity’. Whereas contemporary art becomes increasingly global and transcultural, Rothwell reports that ‘Desert men and women of senior rank want to keep their traditions strong, and more and more to build a fence around the secrets of their law’. It seems that contemporary Western Desert painting has abandoned its original radicalism and returned to a sort of primitivism that is alien to the paradigms of contemporary art. Even some urban Indigenous artists have accused it of doing this. Where does this leave Western Desert painting today, in the age of the contemporary?

Ian McLean is Senior Research Professor of Contemporary Art at the University of Wollongong. He has published extensively on Australian art and particularly Aboriginal art within a contemporary context. His books include How Aborigines Invented the Idea of Contemporary Art, White Aborigines Identity Politics in Australian Art, and Art of Gordon Bennett (with a chapter by Gordon Bennett). He is a former advisory board member of Third Text, and currently on the advisory boards of World Art and National Identities.

McLean investigates the transculturation of colonial cultures, particularly as they manifest in Australian visual art. He is currently researching intersections that have occurred between Australian Indigenous and Western artists in historical and contemporary contexts.

Poles Apart: Realism and Figurative Abstraction as Modes of Modernity among Mid 20th Century South African Artists

Anitra Nettleton, University of the Witwatersrand/Witwatersrand Art Museum

Among indigenous South African artists pure abstraction had little traction, despite long-standing abstract mural and beadwork traditions in many communities. In the early 20th century modernity among indigenous artists was measured against European standards of realism and naturalism, and one of the most fêted isiZulu-speaking artists among educated indigenes, Gerard Bhengu, produced drawings in a style of heightened naturalism and chiaroscuro that astounded settler audiences that thought Africans incapable of producing naturalistic images. Bhengu, whose reception in high arts circles was less positive than his popular profile suggested, was nevertheless specifically celebrated by members of the western-educated intellectual elite among isiZulu-speakers as a modern African. His realism, like that of Hezekiel Ntuli, an artist who produced busts of indigenous subjects in unfired clay, thus stands in a very different relationship to modernity, from the position occupied by ‘heads’ produced by two self-consciously modernist artists of the mid-20th century, in which figurative abstraction was the predominant mode. Ezrom Legae and Sydney Kumalo produced these images in the mid 1960s, with undoubted echoes of Moore and Ernst, but in a style of figurative abstraction that deliberately aspired to modernity via a reengagement with Modernism and African forms. In an examination of selected works I argue that in these seemingly completely opposed modes of modernity there is, however, a strong thread that insists on an African identity that is both local and shared across different spaces.

Anitra Nettleton is Director and Chair of the Centre for the Creative Arts of Africa at the University of the Witwatersrand, and Academic Head of Witwatersrand Art Museum. She earned the first PhD in South Africa on, and is a leading scholar in, the field of African art studies. Author of African Dream Machines: Style and Meaning in African Headrests, (2007), she has published widely on the indigenous arts of Southern Africa in journals including African Arts and Visual Studies. She has also published on contemporary African artists in Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art, Art South Africa and African Arts, as well as in a number of exhibition catalogues. With the Wits Art Museum staff she has co-curated a number of exhibitions, and recently a section of the UCLA Fowler Museum’s 50th anniversary show. Her concern with modernity is reflected in concurrent work on modern traditions and traditions of modernism in South African art.

After Modernism: El Anatsui’s Metal Sculptures and Sankofa Ideology

Chika Okeke-Agulu, Princeton University

The Nigerian-Ghanaian artist El Anatsui has, in the past decade, attained global acclaim for his monumental metal sculptures that have variously been compared with Akan Kente Cloth, the paintings of Gustave Klimt, modernist mobile sculpture, and cutting-edge relational objects. My task in the paper is not to argue against these readings. Rather I seek to situate these metal sculptures within Anatsui’s oeuvre, which includes important though lesser known works in other media but which illuminate the artist’s relationship at the beginning of his career with Sankofa, the modernist political ideology promoted by Ghanaian first president and leading Pan-Africanist Kwame Nkrumah. My reading of the recent work suggests how it reflects Anatsui’s shifting yet enduring relationship with the spirit of Sankofa, and how this might instantiate the different stakes of and connections between modernism and contemporary art.

Chika Okeke-Agulu specialises on classical, modern, and contemporary African art history and theory. He previously taught at The Pennsylvania State University, Emory University, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, and Yaba College of Technology, Lagos. In 2006, he edited the first ever issue of African Arts dedicated to African modernism, and has published articles and reviews in African Arts, Meridians: Feminism, Race, Internationalism, Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art, Art South Africa and Glendora Review. He contributed to edited volumes such as Reading the Contemporary: African Art from Theory to the Marketplace, The Nsukka Artists and Contemporary Nigerian Art, and The Grove Dictionary of Art. Professor Okeke-Agulu is a recipient of the Arts Council of the African Studies Association Outstanding Dissertation triennial award (2007). In 2007, Professor Okeke-Agulu was appointed the Robert Sterling Clark Visiting Professor of Art History at Williams College, and Fellow at the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute. He is also on the faculty of the Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University.

‘Another Part of the Circle’: Positioning the Native Modern and the Contemporary Indigenous In and Out of (Art) History

Ruth B. Phillips, Carleton University

During the past fifteen years, modern works by Canadian Aboriginal artists have moved rapidly into prominent positions in temporary and permanent exhibitions in Canada’s largest and most prestigious art galleries. Although this change in institutions, which had previously excluded Indigenous arts from their mandates, appears sudden and dramatic, it is the product of many years of Aboriginal activism and reflexive and postcolonial academic critique. The new inclusivity, however, raises new questions about art-historical habits of temporal positioning, particularly in relation to the founding generation of modern artists. This lecture explores the intergenerational relationships of modern and contemporary artists by examining a series of works made to pay explicit homage to the founding figure of modern Canadian Aboriginal painting, Norval Morrisseau. Made by both 20th and 21st century artists whose styles and practices are highly diverse, they collectively constitute a remarkable affirmation of an artist whose work was excluded from major art museums until very recently. The artists’ conceptualisations of their debt to Morrisseau suggest another way to think about the modern and the contemporary, which remains historical while resisting both the retention of a categorical division and its erasure. This third way takes its cue from the Indigenous concept of time articulated by Cree playwright Tomson Highway in his description of life and death as a journey to ‘another part of the circle.’

Ruth B. Phillips holds a Canada Research Chair in Aboriginal Art and Culture and is Professor of Art History at Carleton University in Ottawa, Canada. Since completing doctoral research on Mende women’s masks from Sierra Leone, she has focused her research and teaching on Indigenous North American art and critical museology. Her books include Museum Pieces: Toward the Indigenization of Canadian Museums (2011)); Trading Identities: The Souvenir in Native North American Art from the Northeast, 1700-1900 (1998); and, with Janet Catherine Berlo, Native North American Art for the Oxford History of Art (2nd ed, 2014). She served as director of the University of British Columbia Museum of Anthropology from 1997-2003 and as president of CIHA from 2004-8. Currently she is working with Norman Vorano on Artists and Mentors: The Emergence of Indigenous Modernisms in Transnational Perspective, a research project supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. She is a fellow of the Royal Society of Canada.

Secrecy and Revelation: Joe Herrera’s Pueblo Modernism

W. Jackson Rushing III, University of Oklahoma

The Cochiti Pueblo Indian painter, educator, and activist Joe Herrera (1920-2001) was a key figure in (Native) American modern art. He began painting as a child under the informal tutelage of his mother, Tonita Peña, the only female artist in the first generation of modern Pueblo painters. By 1940 he was making flat, decorative watercolors of Pueblo life. After service in World War II, Herrera made studious copies of Pueblo pottery designs, which reinforced his interest in precise linearity and the abstract character of design and decoration. At the University of New Mexico in 1950 the modernist Raymond Jonson introduced him to Art Deco, Cubism, and Paul Klee’s primitivism. In addition, Herrera studied ancient and historic material in situ at archaeological excavations. The result, Herrera’s pictographic Pueblo modernism, or what he called ‘abstract symbolism,’ was a game-changer. By 1952 he was being celebrated for demonstrating ‘the fact that current American Indian painting . . . can be entirely modern’ (Dunn 1952). In 1954 he was awarded Les Palmes Academique by the French Academy for his artistic achievement.

From the late 60s through the early 90s Herrera made dramatic images of ancient ceremonies, often based on murals found in kivas (underground ritual chambers). Balanced on the fulcrum between realism and abstraction and between secrecy and revelation, such paintings, I propose, are the aesthetic equivalent of his political advocacy and his efforts at cross-cultural education. The elaborate iconography of these late works and its ethical implications for my art historical methodology are the endgame of this paper.

W. Jackson Rushing III is Adkins Presidential Professor of Art History and Mary Lou Milner Carver Chair in Native American Art at the University of Oklahoma. He works in several intersecting areas: Native American art; modern and contemporary art; Southwest modernism; theory, criticism, and methodology; museum studies; and post-colonialism and visual culture. His teaching and scholarship explore the interstitial zone between (Native) American studies, anthropology, and art history. For more than twenty years now he has pursued a duality—Native-inspired modernist primitivism and indigenous modernism in the United States and Canada. Rushing is the author of Native American Art and the New York Avant-Garde (1995), Teresa Marshall: A Bed to the Bones, (1998) and Allan Houser: An American Master (2004); editor of Native American Art in the Twentieth Century (1999) and After the Storm (2001); and co-author of Modern By Tradition (1995), which received The Southwest Book Award. He has lectured widely in Canada, the U.S. and the U.K., and been a Director of the College Art Association of America.

Choice!, Contemporary Māori art and a Crisis of National Identity

Lara Strongman, Christchurch Art Gallery

In 1990, New Zealand marked the 150th anniversary of the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi. It was a year in which the symbolic expression of nationhood collided with the exigencies of contemporary history. Prompted by profound economic, social and cultural transformations associated with globalisation and decolonisation, New Zealand’s late twentieth-century crisis of national identity was strongly articulated by contemporary art practice of the early 1990s, spearheaded by the new Māori art which remixed local modernisms with global cultures.

If modernism and mid-century cultural nationalism in Aotearoa New Zealand arguably amounted to very much the same thing, implicit in the local post-modernist project was pressure brought to bear on an essentialising notion of national identity from a newly visible range of subject positions. This paper argues for the importance of Choice!—an exhibition of work by contemporary Māori artists curated by George Hubbard and Robin Craw in 1990—in initiating a national discussion about the politics of identity in the visual arts. It focuses in particular on Michael Parekowhai’s The Indefinite Article (1990), which restaged in three dimensions the textual elements of a painting by Colin McCahon from 1954. For a younger generation of New Zealand artists in the early 1990s, McCahon represented the modernist past. While his work was variously referenced, appropriated and recontextualised by them as a means of expressing the distance and difference of the contemporary, it was also deployed by Parekowhai and others to articulate new identities.

Lara Strongman is senior curator at Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetu. She was formerly senior curator/deputy director at City Gallery Wellington. Her PhD (Victoria University of Wellington, 2013) explored the contested relationship of high and mass culture in New Zealand. She co-edited Parihaka: The Art of Passive Resistance, which won the history and biography category of the national book awards in 2002; and Contemporary New Zealand Photographers, which won the illustrative category in 2006. In 2003 she curated the first major survey exhibition of Shane Cotton’s work, for City Gallery Wellington. She is currently working on the reopening programme of Christchurch Art Gallery, closed since the 2011 Christchurch earthquakes.

Staring at Motorways: Urban Pacific Art– a Genealogy of Sorts

Nina Tonga, Pacific Cultures curator, Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, Wellington, New Zealand

The title of this paper is derived from the comments of artist, curator and writer Rosanna Raymond a core member of the Pacific Sisters, a collective of Pacific Island and Māori artists, designers and models who began working together in the early 1990s. In speaking of the influence of the collective’s multidisciplinary practice that included fashion, pageants and performances she stated that ‘we don’t stare at coconut trees – we stare at motorways’. Raymond’s statement is indicative of the urban environment from which a generation of New Zealand-born Pacific artists emerged in the 1990s and for whom the Pacific existed as a kind of here, there and elsewhere. For some of these artists the sense of dislocation provided the impetus for new identities as well as an aesthetic that reflected their Pacific heritage and the urban realities of living in Aoteroa – specifically Auckland. By examining art works by a range of Pacific artists including Pacific Sisters and Andy Leleisi’uao, this paper seeks to trace the routes/roots of urban Pacific art that emanate from this time and place. How do we understand ‘urban pacific art’ of this time? Furthermore how does it relate to the ongoing currency of the ‘urban’ in contemporary Pacific art?

Nina Tonga is Curator Pacific Cultures at Te Papa. She holds a Master of Arts specialising in contemporary Pacific art and is a doctoral candidate in the Department of Art History. Her current research focuses on contemporary Pacific art in New Zealand and the Pacific with a particular interest in internet art from 2000 to present. Nina has been involved in a number of writing and curatorial projects with Pacific artists from New Zealand and the wider Pacific. In 2012 she was an associate curator for the exhibition Home AKL, the first major group exhibition of contemporary Pacific art developed by Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki. Other curatorial projects include Koloa et Al at Fresh Gallery Otara, Make/Shift at St Paul Street Gallery and most recently Tonga ‘i Onopooni: Tonga Contemporary at Pataka Museum, Wellington.

Back to the Future: Terry Ryan in Cape Dorset

Norman Vorano, Queen’s University

The earliest cultural intermediaries who worked with the graphics studio in the Canadian Arctic community of Cape Dorset in 1957 embraced a form of ‘modernist-primitivism’ that exploited the well-worn discursive pathways of the early 20th century art-world, when non-Western arts first became entangled in the Western art-culture system due to the interest of avant-garde artists and collectors. By 1965, there was a gradual but perceptible shift in the way artists in the Cape Dorset studio attempted to position themselves in the larger art-world, conceptualising ‘time’, ‘modernism’ and ‘contemporaneity’ in ways that tried to overcome the inherent contradictions of modernist primitivism. Under the direction of Terry Ryan, a Toronto-born artist hired by the Inuit artists in 1961 to be the resident arts advisor, there is a marked effort to move away from the then-dominant narratives of modernism and define a logic of practice that draws from and acknowledges Inuit traditional knowledge while declaring the artist’s coevality with the mainstream world. This paper looks at the biographical and historical forces that shaped Ryan’s engagement with the artists in Cape Dorset—in particular a dog-sled trip he took to the North Baffin region in 1964—and identifies the key elements of this transition that, in intriguing ways, foreshadows some of the tenets of the ‘global contemporary’ today.

Norman Vorano is a National Scholar and assistant professor in art history at Queen’s University, Canada. From 2005 to 2014, he was the Curator of Contemporary Inuit Art at the Canadian Museum of History [formerly Canadian Museum of Civilization], Canada’s national museum. Vorano received his PhD from the Program in Visual and Cultural Studies, University of Rochester, NY, with a dissertation that critically examined the production, consumption and exhibition of Inuit carving in the mid-twentieth century. He has researched and published on emerging and senior contemporary artists in Cape Dorset, Pangnirtung and in urban centres in southern Canada. His 2011 exhibition (co-curated with Ming Tiampo and Asato Ikeda), Inuit Prints, Japanese Inspiration: Early Printmaking in the Canadian Arctic, examined the historical linkage between Japanese printmaking and Cape Dorset printmaking in the late 1950s. He is now working on a project involving mid-twentieth century graphic arts from the North Baffin Region.

Resisting Modernism: Strategies within Contemporary Māori Art

Anna-Marie White , Curator, The Suter Gallery, Nelson

Recent histories of Māori art have focussed attention on the first generation of Māori artists to practice according to the European modernist tradition. This mid-20th century movement has been described as Māori Modernism, and is associated with the social process of Māori urbanisation and European cultural assimilation and the rejection of customary Māori art forms. These art histories emphasise points of engagement with international modernist discourse and have achieved a significant recognition for Māori artists in New Zealand art history. However, Māori Modernism remains a Eurocentric frame and has the potential to subsume the work of successive generations of contemporary Māori artists as a strand of the New Zealand and European art historical traditions.

This paper focuses on the work of three contemporary Māori artists who resist modernism as the beginning of contemporary Māori art history. Rather, Robert Jahnke, Brett Graham and Saffronn te Ratana observe a different whakapapa (lineage) for contemporary Māori art. They draw attention to earlier examples of artistic rupture and Māori appropriation of Western traditions; instances when Māori confronted change from a position of economic and political power and for the purposes of tino rangatiratanga (self-determination). In this regard their work provides an alternative and empowering history that disturbs the hegemony of Māori Modernist discourse.

Anna-Marie White (Te Ātiawa) is the curator at The Suter Art Gallery Te Aratoi o Whakatū, Nelson, New Zealand. She has a Master of Arts in Museum Studies (first class honours) from Massey University, which investigated the practice of Māori curatorship at Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki. Her most recent project was Kaihono Āhua / Vision Mixer 2013; an experiment in bicultural curatorial practice comprising two exhibitions that compared recent trends in the work of Māori and Pākehā artists. This vision of biculturalism remixed the stereotypes of Māori and Pākehā culture; framing Māori as Modernists and Pākehā as Primitive to create a provocative political experience that challenged perceptions of identity in New Zealand art.

CONVERSATIONS

In Conversation: Richard Bell, Josh Milani, and Ian McLean (moderator) on appropriation, modernism, and indigenous art in the contemporary field

This conversation is in honour of Gordon Bennett, 1955–2014

Documenta is the preeminent exhibition of contemporary art. Its Artistic Directors are expected to develop an argument that foregrounds the art speaking to us today. Most of the artists in the most recent Documenta (in 2012) were born in the 1970s. What did it mean, then, when its Artistic Director Carolyn Christov-Barkagiev also included a substantial display of paintings in adjoining rooms by two women modernists born in the 1870s, the Canadian Emily Carr and the Australian Margaret Preston. These artists shared two things: both pioneered modernist art in colonial places on the periphery of modernism’s European centres, and each were inspired by Indigenous art. Christov-Barkagiev’s intention was clearest in respect to Preston, as next to her paintings were large appropriations by Gordon Bennett of designs that Preston had appropriated from Indigenous shields. Bennett’s double appropriations had followed, to the letter, Preston’s instructions for developing a distinctive Australian modernism.

To discuss the significance of these issues of appropriation, modernism and Indigenous art in the field of contemporary art are Richard Bell, whose art has addressed these issues for many years, Josh Milani, the Director of Milani galleries, who represents Bennett and Bell and has been in the forefront of positioning Australian art in an international context, and Ian McLean, who has written extensively on these issues.

Richard Bell (b. 1953) lives and works in Brisbane, Australia. He works across a variety of media including painting, installation, performance and video. One of Australia’s most significant artists, Bell’s work explores the complex artistic and political problems of Western, colonial and Indigenous art production. He grew out of a generation of Aboriginal activists and has remained committed to the politics of Aboriginal emancipation and self-determination. In 2003 he was the recipient of the Telstra National Aboriginal Art Award, establishing him as an important Australian artist. Bell is represented in most major National and State collections, and has exhibited in a number of solo exhibitions at important

institutions in Australia and America. In 2013 he was included in the National Gallery of Canada’s largest show of International Indigenous art, Sakàhan: International Indigenous Art, and at the Fifth Moscow Biennale of Contemporary Art. In 2014, Bell’s solo exhibition Embassy opened at the Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts, Perth.

Ian McLean (see Speakers above).

In Conversation with Katharina Greven, Chika Okeke-Agulu and Nicholas Thomas about the legacy of Georgina Beier and Ulli Beier in Nigeria and Papua New Guinea

Ulli Beier (1922-2011) and Georgina Beier (b 1936) were catalysts for, and key supporters of literature, theatre and visual art in Nigeria, Papua New Guinea, and elsewhere from the 1950s onwards. In 1957, Ulli founded Black Orpheus, which became a key publishing outlet for Wole Soyinka and Chinua Achebe among others. Georgina ran the Oshogbo art workshops between 1963 and 1966 before they moved to Papua New Guinea, where they were similarly closely involved with key figures in a culture of decolonisation. Ulli mentored writers such as Albert Maori Kiki while Georgina ran painting, printmaking and textile printing workshops, and encouraged a range of artists including Akis, Mathias Kauage and Ruki Fame – the founding figures of modern Melanesian art. Over the next 30 years they continued to travel between Nigeria, Papua New Guinea, Australia and Germany, promoting a new culture appropriate to the newly independent nations.

This conversation will range over their work in west Africa and the Pacific, reflecting on the Beiers’ roles as radical expatriate mentors over formative decades for the emergence of artistic modernism and postcolonial culture in the regions concerned.

Katharina Greven is a Junior Fellow atBayreuth International Graduate School of African Studies, University of Bayreuth. The focus of Katharina’s PhD, which she started in October 2012, is on images created by art patrons in Africa in the Modern epoch. Before that she was one of the deputy directors of Iwalewa-Haus, the Africa center of the University Bayreuth and prior that she worked at the Goethe-Institute Nairobi for three years as program-assistant with responsibility for exhibitions, literature and publications. She studied free art (focus: photography) at the art academy in Düsseldorf with Thomas Ruff, Peter Doig and George Herold, became ‘Meisterschüler’ in 2006, graduated with a diploma in 2007, then studied ‘African Language Studies’ with a focus on Swahili and sociolinguistics for her master ́s degree, which she completed in 2012.

Nicholas Thomas first visited the Pacific in 1984 to research his PhD thesis on the Marquesas Islands. He has since written extensively on art, empire, and related themes, and curated exhibitions in Australia, New Zealand, and the UK, many in collaboration with contemporary artists. His books include Entangled Objects (1991), Colonialism’s Culture (1994), Possessions: Indigenous Art/Colonial Culture (1999), and Islanders: the Pacific in the Age of Empire (2010), which was awarded the Wolfson History Prize. Since 2006, he has been Director of the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology in Cambridge, which was shortlisted for the Art Fund’s Museum of the Year Prize in 2013.

Chika Okeke-Agulu (see Speakers above).

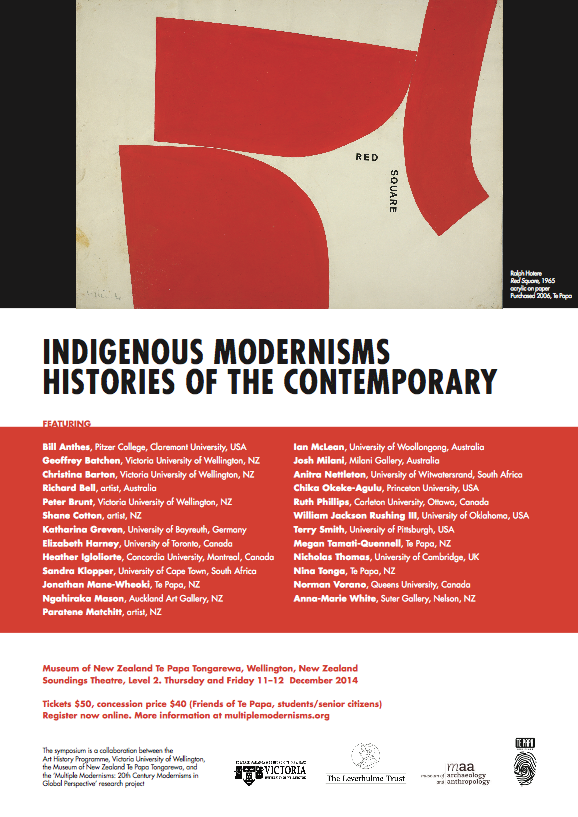

In Conversation: Paratene Matchitt, Shane Cotton, and Megan Tamati-Quennell (moderator) on the influence and impact of the late Ralph Hotere

‘Everything Hotere touches turns to black’, David Eggleton’s witty comment on the late Ralph Hotere, highlights one of the predominant concepts of Hotere’s work and offers a useful starting point for a conversation about his impact and influence within New Zealand and Maori art. Ralph Hotere is a Senior Maori artist, a first-generation contemporary Maori artist and a key figure in the development of Modern Maori art. He was the first Maori artist to be recognised by the New Zealand art mainstream with his work being included in the Auckland City Art Gallery’s annual exhibition Contemporary New Zealand Painting in 1961 and for a long time was the only Maori artist acknowledged within the art mainstream. Hotere was also our first ‘Maori International’ leaving New Zealand in 1961, to take up a scholarship that supported him to study at the Central School of Art in London, a residency in the South of France the following year and travel to Italy. Hoterereturned to New Zealand in 1965 and never really left again. His time overseas 1961-1965 was a formative period in his career during which he established his mature style.

To discuss Hotere’s work are Paratene Matchitt, Shane Cotton and Megan Tamati-Quennell. Para Matchitt in an important figure in contemporary Maori art, a contemporary Hotere‘s and one of a group of senior Māori artists (including Hotere), credited with being the founders of the contemporary Māori art movement. Shane Cotton is a leading artist of his generation. It could be said that Cotton and his contemporaries, second-generation contemporary Maori artists are the inheritors of the achievements of the Māori modernists. Megan Tamati-Quennell, is the Curator of Modern and Contemporary Māori and Indigenous art at Te Papa and the curator of Te Ao Hou, Modern Māori art, a series of projects within Nga Toi, Arts Te Papa specifically focused on the work and practice of the modern Māori artists and their contemporaries.

Paratene Matchitt is an important figure in contemporary Māori art, a pioneering Māori artist whose practice spans six decades beginning in the late 1950s. He is a painter, sculptor and printmaker. Matchitt and his contemporaries are now often referred to as the ‘Māori Modernists’, a name that relates to the first group of Māori artists to engage with the styles and forms of international modern art. Matchitt’s peers were Ralph Hotere, Arnold Wilson, Selwyn Muru, Muru Walters, Fred Graham, Katarina Mataira, Cath Brown and Buck Nin Together and separately they were formative in their reinvigoration of Māori motifs and their personal/contemporised interpretations of Maori concepts and world views.

Shane Cotton is a major New Zealand painter. Born in Lower Hutt with Ngapuhi iwi affiliations, he studied at the Ilam School of Fine Arts in Christchurch, graduating in 1988. He then lectured at Massey University Te Putahi-a-Toi, Māori Visual Arts, in Palmerston North until 2005. Cotton’s work has played a central role in shaping New Zealand’s postcolonial discourse, but he is also an artist who defies easy categorisation, consistently reinventing his own painting practice in the search for new ideas and forms.

A major survey of Cotton’s work was exhibited at City Gallery Wellington and Auckland Art Gallery in 2003. Cotton’s many awards include the Frances Hodgkins Fellowship (1998); the Seppelt Contemporary Art Award (1998); and the Te Waka Toi Award for New Work (1998, 1999). His work is represented in major collections, notably Te Papa Tongarewa Museum of New Zealand; Auckland Art Gallery; the Chartwell Collection; Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney; National Gallery of Australia, Canberra; National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne; and Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane. Shane received a Laureate Award from the Arts Foundation in 2008. Shane received an ONZM (Officer of the said Order), for services to the Visual arts, in the 2012 Queen’s Birthday Honours.

Megan Tamati-Quennell is the Curator of Modern & Contemporary Maori & Indigenous Art at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. She is a leading curator in this field which she describes as art made between indigenous practice and the mainstream. She has specialist interests in the work of the post war (1945) first generation Maori artists, Mana wahine; Maori women artists of the 1980s and 1990s, the ‘Maori Internationals’; the artists that developed with the advent of biculturalism, a postmodern construct peculiar to New Zealand and International Indigenous art with particular focus on modern and contemporary Indigenous art in Australia, Canada and the United States. Tamati-Quennell has an expansive curatorial practice, which spans 24 years. Significant recent projects include a touring exhibition of Ralph Hotere and Michael Parekowhai’s work – Black Rainbow (2014) Gifted Aboriginal Art 1976 – 2011 (2012), Retorts and Comebacks: Peter Robinso (2014) and New Zealand curatorial advisor for the first major survey of international indigenous – Sakahan; International indigenous art (2013), held at the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa.

In Conversation with Terry Smith, Ruth Phillips, Shane Cotton, Christina Barton, Chika Okeke-Agulu, Elizabeth Harney and Geoffrey Batchen (moderator) about Indigenous Art and the Contemporary Art World

Terry Smith is Andrew W. Mellon Professor of Contemporary Art History and Theory in the Department of the History of Art and Architecture at the University of Pittsburgh, and Distinguished Visiting Professor, National Institute for Experimental Arts, College of Fine Arts, University of New South Wales. He was the 2010 winner of the Mather Award for art criticism conferred by the College Art Association (USA), and recipient of the 2010 Australia Council Visual Arts Award. From 1994–2001 he was Power Professor of Contemporary Art and Director of the Power Institute, Foundation for Art and Visual Culture, University of Sydney. He was a member of the Art & Language group (New York) and a founder of Union Media Services (Sydney). Smith’s current work explores the relationship between contemporary art and its wider settings, within a world picture characterised by its contemporaneity. He is the author of many books including Transformations in Australian Art, vol. 2. The 20th Century: Modernism and Aboriginality (Craftsman House 2002); What is Contemporary Art? (Chicago 2009); Antinomies of Art and Culture: Modernity, Postmodernity and Contemporaneity (co-edited with Nancy Condee and Okwui Enwezor (Duke 2008) and Contemporary Art: World Currents (Pearson 2011).

Christina Barton is Director of the Adam Art Gallery at Victoria University of Wellington. She is an art historian, curator, and editor known for her work on the history of post-object art in New Zealand. She has held positions at Auckland Art Gallery (1987-1992) and the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (1992-1994) and as Senior Lecturer in Art History at Victoria University of Wellington (1995-2007). Key exhibitions she has curated include After McCahon: Some Recent Configurations in Contemporary Art (Auckland Art Gallery, 1989); Art Now: The First Biennial Review of Contemporary Art (MoNZ, 1994); Close Quarters: Contemporary Artists from Australia and New Zealand (touring Australia and NZ, 1995); Joseph Kosuth: Guests and Foreigners, Rules and Meanings (Te Kore)(Adam Art Gallery (AAG), 2000); The Expatriates: Frances Hodgkins and Barrie Bates (AAG and Gus Fisher Gallery, 2004-5); Four Times Painting (AAG, 2007); Hydraulics of Solids: João Maria Gusmão & Pedro Paiva (AAG, 2008); The Subject Now (AAG, 2008); I, HERE, NOW Vivian Lynn (AAG, 2008-9); Billy Apple New York 1969-1973 (AAG, 2009).

Geoffrey Batchen is Professor of Art History at Victoria University of Wellington. He focuses on the history of photography, with a particular interest in the way that photography mediates every other aspect of modern life, whether talking about sex or war, atoms or planets, commerce or art. Batchen is the author of Burning with Desire: The Conception of Photography (1997), Each Wild Idea: Writing, Photography, History (2001), Forget Me Not: Photography and Remembrance (2004), William Henry Fox Talbot (2008), What of Shoes: Van Gogh and Art History (2009), and Suspending Time: Life, Photography, Death (2010). He has also edited an anthology of essays titled Photography Degree Zero: Reflections on Roland Barthes’s Camera Lucida (2009) and co-edited another titled Picturing Atrocity: Photography in Crisis (2012). He has a long involvement with the international art world as a curator and editor. He has taught in a number of tertiary institutions in Australia and the US, including the University of California San Diego, the University of New Mexico and the Doctoral Program in Art History at The Graduate Center of the City University of New York.

Ruth Phillips (see Speakers above).

Shane Cotton (see Conversation above).

Chika Okeke-Agulu (see Speakers above).

Elizabeth Harney (see Speakers above).

The symposium was held at Te Papa Tongarewa/Museum of New Zealand, Wellington, New Zealand.